Hunt at night, hide at day

Aerial acrobats

Eurasian nightjars are among the few insect-eating birds that hunt the skies in the dead of night. The species has increased in numbers in most of the breeding range, which mainly consists of relatively acidic heathlands, but it remains largely unknown what caused this uplift.

They soar over open areas and along forest edges to pursue insect prey in the air with high agility, for which their wings are suited. The hand wing is long and the arm is short, the thumb feathers are large and the tail is long, all enabling sudden movements to chase insects.

To withstand the forces of such sudden turns, the wing muscles are very strong and attach to a high-keeled sternum, with an extra ridge for muscle attachment on the back end. The tail muscles are heavily built, providing strength for the tail during such manoeuvres. A powerful flight also becomes convenient for the migration to Eastern Africa to spend the winter there.

Flying beak

Eurasian nightjars detect their prey on sight, for which they have enormous eyes positioned in the sides of their head to create a large field of view. Their bill seems very small when closed, but when opened, it becomes apparent that nightjars are designed to function as a “flying beak”, also reflected in the flat, wide skull. The lower jaw is very flexible and can be stretched to enlarge the mouth opening.

Strong bristle feathers in the corners of the beak help directing prey towards the mouth and may keep prey from escaping. A comb-like structure on the middle toe nail is suggested to be used in cleaning these bristles, although this behaviour cannot be found in footage.

Double camouflage

Eurasian nightjars breed on the ground, with which their cryptic plumage blends in perfectly. Although the large webbing between the toes enlarges the foot surface and the heel is equipped with leathery scales for grip and protection, their legs are not fully adapted to a life on the ground.

Continue reading

The lower leg is short and the middle and hind toes are long, designed to grasp branches, which they often do in small trees or bushes. From such lookouts, potential prey is observed and their powerful and characterising song of the heathlands is often sung.

The camouflage of males is breached by conspicuous white spots on the wing and tail tips, which are shown during gliding display flights at dusk. In these aerial courtships the wings loudly strike together, while singing their typical, persistent churring song.

Eurasian nightjars possess another form of camouflage, invisible to the human eye, also found in e.g. owls. Their feathers can absorb UV-light, which makes the feathers look dark-shaded, helping them to blend in with the darkness for birds that can see UV-light. This technique could keep them unnoticed from larger nocturnal predators, like tawny owls, hunting upon nightjars in turn.

Multi-purpose grit?

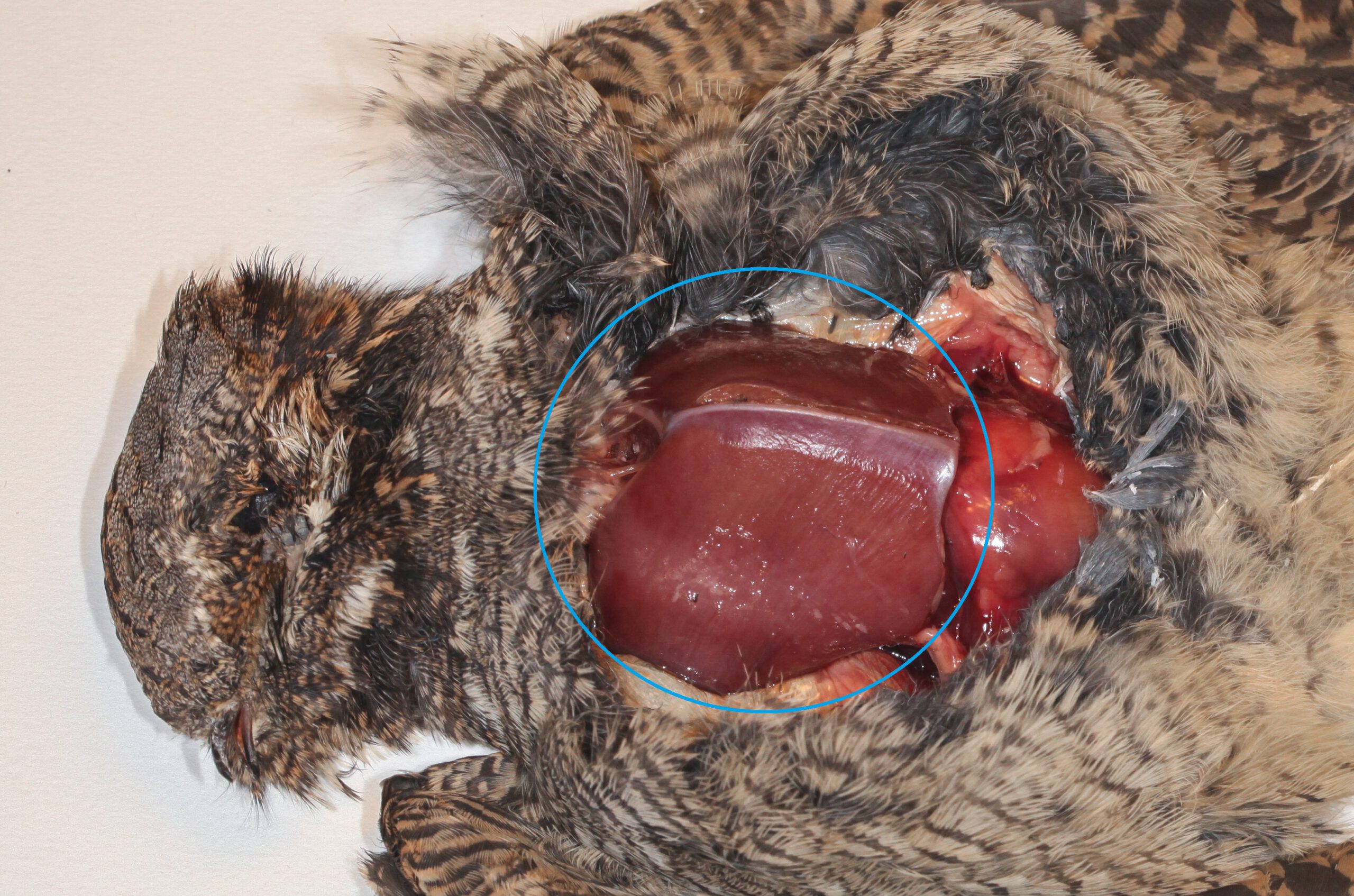

The insectivorous diet of nightjars is easy to digest and allows a short digestive system, for which their relatively small torso and short pelvis offer enough space.

Although the stomach is small, it is very muscular and has a thick wall, which may be necessary to crush large, armoured prey, like mantises or longhorn beetles. Pebbles and grit are swallowed and remain inside the stomach, like in many birds, and help crushing prey.

Additionally, grit could serve as an important solution for nightjars to cope with decreased calcium levels in their acidified habitat, particularly when they need extra calcium to produce egg shells in reproductive season. Alternative calcium resources may be scarce or difficult to obtain, which is experienced by passerines living in the same habitat, like wheatears or larks.

Eurasian nightjars have a proportionally short intestine and two large, club-shaped blind guts, which may increase the efficiency of digestion by recycling uric acid waste, comparable to a feature found in owls.