Long legs and a long bill: best of both worlds?

Black-tailed godwits announce spring with their return to the pastures and grasslands of Northern Europe after a long flight from Africa. Their long and pointy wings and a strong, high-keeled breastbone with large flight muscles enable a fast and active flapping flight, in order to reach their breeding grounds from southern Spain in a single non-stop flight (but some may also make stops along the route).

Impacts of agricultural shift

Although the black-tailed godwit is the National Bird of the Netherlands, with 80% of the world population nesting in this country, their numbers have dropped drastically due to changes in the agricultural system.

As a result of these changes, grasslands have become insect-poor monocultures, which are also mown too early in the season, destroying nests and offspring. Additionally, ground water tables are artificially kept low, which has an impact on the feeding behaviour of adults, as is explained further on.

Long bills of all sorts

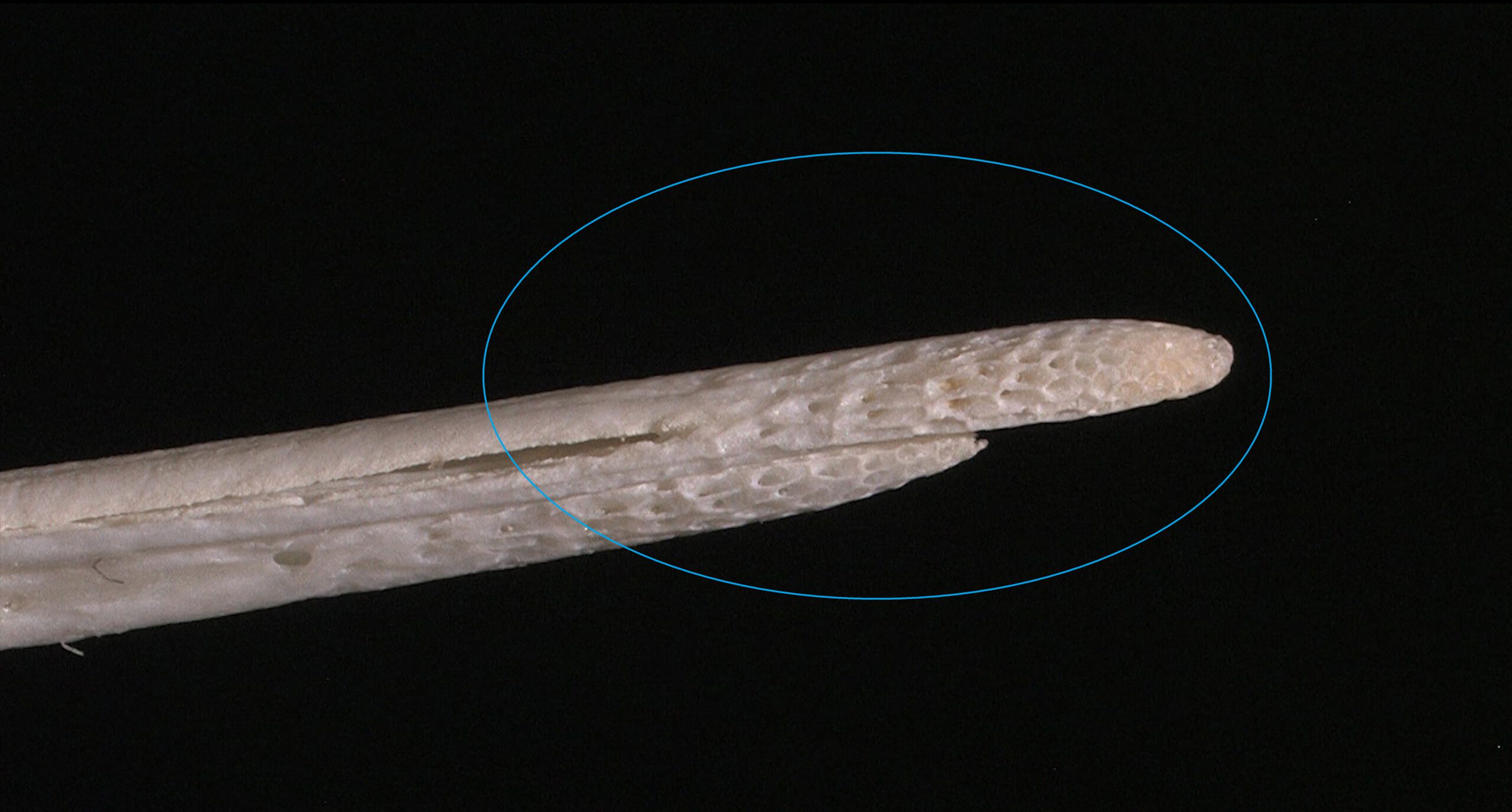

Most of the food of the adults, like insect larvae, worms, molluscs, rice or other seeds, is hidden beneath the soil surface, sometimes also covered by shallow water. Godwits probe the soil with their long bill and detect a potential meal on touch by dozens of sensory nerve endings in the bill tip, recognized as pores in the bill tip bone. To grasp their food in the soil without too much resistance, the bill tip can be opened like a pair of tweezers, while the rest of the bill remains closed. This is possible thanks to a specially adapted skull, with a cheekbone that is elongated right up to the bill-tip.

This technique is also found in other probing birds like Eurasian woodcock, but is absent in long-billed waders that use their bills as a hammer (like oystercatchers) or as curved tool to retrieve prey from cavities in soil or rocks (like curlews). This video shows how a godwit’s and a curlew’s bill are differently built and therefore enable different feeding techniques. A long tongue eventually helps swallowing the food item. Black-tailed godwits can only perform the pincer-movement of the upper bill if the ground is soft, as in flooded soils. Hence, low ground water tables and dried-out soils are problematic for foraging adults.

Best of both worlds

Although godwits are often associated with water, their toes of moderate length and with minimal webbing reveal that they are not well-adapted to live in swamps or to go about swimming. Their long legs are useful to feed in shallow water, but also to walk among high grasses, which the birds prefer to build a well-concealed nest. Longer legs allow higher water to forage in, but also require a longer and stronger neck and bill in order to reach prey below-ground.

Contrastingly, long legs are no advantage when feeding on dry soils. This means godwits have optimised their body plan over time to benefit most from both worlds. Waders picking insects from the water surface are not restricted by foraging on or in the ground and therefore can have longer legs, of which stilts are the most extreme example.

Continue reading

Adapted from the very beginning

Even the posture in which chicks lay inside the egg is specially adapted to give space to the long legs and bill. Almost directly after hatching, the fledglings actively forage by themselves on mobile prey like insects in the cover of tall pasture vegetation, for which they need long legs and a long bill. The pointed end of the egg houses the long leg bones, and the head (covered by feet) is positioned centrally in the egg instead of at the air chamber, allowing a longer bill at hatching.

Changeable digestive system

Invertebrates comprise the main components of a godwit’s diet in the breeding season, but on migration and during the winter the diet becomes dominated by plant material, which can consist almost completely out of rice seeds. This variation in diet requires adaptations in the digestive system, such as an adjustable gut length, in order to efficiently process these different food types.

Several organs may become significantly larger or smaller, depending on the season or stage. Large digestive organs are needed to store as much energy in a short time, for instance prior to or after migration, but small digestive organs are beneficial to be as light-weight as possible during the long flight to Africa.

A strong, muscular stomach with some small stones inside helps crushing plant seeds, molluscs or hard insect parts. The intestine is long in order to efficiently digest the food and absorb the nutrients. Blind guts of substantial size are also present, which could either aid in the digestion of plant material in winter, or, similar to e.g. owls, help to recycle uric acid, the main waste product of the kidneys.